In modern times, June is a favorite month for celebrating weddings, so it is only fitting that today we remember the fateful union of Matilda, the widowed Empress of the Holy Roman Empire, and Geoffrey V, Count of Anjou, Touraine, and Maine, on June 17, 1128.

Even in a time when the desires and preferences of the betrothed couple did not matter, this was a union with few prospects for marital happiness.

Matilda was 26 years old. She was the granddaughter of William the Conqueror and daughter of Henry I, King of England and Duke of Normandy. Her first husband had been Henry V, the Holy Roman Emperor, and she would proudly retain the title of “Empress” for the rest of her life. She had spent her life at various centers of power, and she had helped her husband rule his vast holdings, particularly as he wasted away from cancer before his death in 1125.

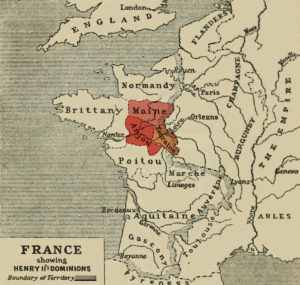

Geoffrey was 14 years and 10 months old on the day of the wedding. He was the son of a provincial count. At the time of his marriage, young Geoffrey had seen little of the world, although he was educated, particularly in military skills. The only thing that recommended him were his family’s landlocked, yet strategic, counties of Anjou, Touraine, and Maine, which were situated along the southern border of Normandy.

This unlikely union was orchestrated by Henry I, who had lost his son and heir in the White Ship disaster of 1120. Henry had two legitimate children with his queen, Matilda of Scotland: Empress Matilda (b. 1102) and William Adelin (b. 1103). The tragic death of William Adelin had left Henry with no legitimate sons.

During this time, the rules of succession were not firmly established, although legitimacy had become a requirement. Therefore, Henry’s nine illegitimate sons could not rule. Matilda of Scotland had died in 1118, so Henry remarried after the death of William Adelin and hoped to sire another son, even though he was now in his 50s.

In the years following his remarriage, Henry’s hopes for a new heir began to dim, and he was faced with impossible choices. His older brother, whom he had imprisoned in order to take control of the Duchy of Normandy, had a son with a valid and widely recognized claim to the throne. Another nephew, Stephen of Blois, was the son of Henry’s sister, and he was also considered a rightful contender for the throne.

But Henry held out hope for another alternative, and it was the death of his son-in-law in 1125 that finally gave him the option of passing the crown to a direct descendant when Matilda returned to her father’s household in Normandy as a childless widow.

During the Christmas celebrations of 1126, Henry decreed that Matilda would be his heir, if he did not sire another son with his new queen before his death. This was a bold decision, as the idea of a woman ruling in her own right was practically unheard of at the time. For this reason, it was imperative that Matilda marry and bear at least one son to overcome the doubts that many had about her as heir to Henry.

In this highly charged atmosphere, Henry chose Geoffrey of Anjou. It was a marriage that would ensure the security of the southern border of Normandy, and the boy was young, healthy, and reputedly intelligent.

Chroniclers from that time report that Matilda was against the marriage, but in the end, like most women of her time and station, she had no real choice. At the time of their betrothal in 1127, Geoffrey was 13, and the couple had to wait a year, since 14 was the accepted age for boys to marry.

On June 17, 1128, they were married in Le Mans. Both were strong-willed and accustomed to getting their own way. Teenaged Geoffrey had much to learn about the world and political maneuverings. The worldly Matilda likely had much to offer in the way of advice and strong opinions. It was a recipe for disaster.

In the autumn of 1129, after fifteen months of marriage, they separated. They were apart for two years, until Henry insisted that Geoffrey and Matilda reconcile. Henry had become increasingly desperate for grandsons who could reassure his barons that the succession would not be solely reliant on Matilda taking the throne.

By the autumn of 1132, Matilda was finally pregnant, and on March 5, 1133, she gave birth to a healthy son, whom she named Henry. In 1154, this son would ascend to the throne as King Henry II, and he would become the founder of the Plantagenet Dynasty, a name that originated with his father, Count Geoffrey. Geoffrey received his nickname from the yellow sprig of broom blossom (planta genista, or broom shrub) that he often wore in his hat.

Two more sons followed: Geoffrey in 1134 and William in 1136.

When Henry I died in 1135, Matilda was pregnant with her third son, and she was unable to move quickly to secure the throne. Her cousin, Stephen of Blois, broke his pledge to support her as Henry’s heir, and he was crowned King of England and Duke of Normandy.

For nearly 20 years, Matilda would fight for her inheritance, and until his untimely death in 1151, Geoffrey would steadfastly support her, even though he had no assurances that he would ever be crowned King of England, should she gain the throne. In 1144, he assumed the title, Duke of Normandy, after his successful military campaigns took the duchy from Stephen. In 1150, he willingly surrendered that title to his 17 year old son, Henry, in order to bolster Henry’s position in the war of succession.

On this day, the 891st anniversary of the wedding of Matilda and Geoffrey, we look back at a marriage that foundered and nearly failed at the beginning. Nevertheless, the marriage was ultimately a success. We will never truly know how Matilda and Geoffrey felt about each other, but we do know that the bond of parenthood created a union of two indomitable people with a shared goal – a crown for their son, Henry.

Bibliography

Chibnall, Marjorie. The Empress Matilda: Queen Consort, Queen Mother and Lady of the English. Oxford: Blackwell, 2011.

Hanley, Catherine. Matilda: Empress, Queen, Warrior. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2019.

Original images are in the public domain. Modifications of public domain images by J. C. Plummer.

Text © 2019 J. C. Plummer

Posted on

Leave a Reply