The Angevins were the first three Plantagenet kings of England: Henry II (the husband of Eleanor of Aquitaine), Richard the Lionheart, and John, the king who famously signed the Magna Carta. But why are these 12th century English monarchs called the Angevins?

This is the story of how a disaster at sea, a widowed empress, and a landlocked county in the heart of France gave rise to a dynasty that would rule England for over three centuries, significantly shaping the future of both England and France.

A Disaster of Titanic Proportions

Nearly 800 years before the H.M.S. Titanic struck an iceberg and plunged to the bottom of the Atlantic, another vessel crowded with the elite of its day met a similar fate.

The details are lost in the mists of time. The legends are many, but they can never be verified. Was the boat dangerously overloaded? Were the passengers engaged in drunken revelry? Was the crew similarly incapacitated? Had the captain been goaded into unsafe speeds in an attempt to overtake a second ship carrying King Henry I of England?

All that is known with certainty is that on 25 November 1120, the White Ship sank in the English Channel off the coast of Barfleur, Normandy. Setting sail after dark, it had struck a submerged rock and capsized. There was only one survivor, and it is estimated that nearly 300 people drowned that fateful night.

Although the sheer number of casualties would be enough to mark the event in the memories of those living at the time, the scope of this disaster would reach far beyond the number of bodies washing ashore the following morning, for this disaster claimed the life of a man who had been destined to rule both England and Normandy. William Adelin, the eldest son and heir of King Henry I, and a grandson of William the Conqueror, was aboard the White Ship, and his death led to a crisis of succession that is known today as the “Anarchy.”

An Empress without an Empire

King Henry I, the youngest son of William the Conqueror, had two legitimate children who survived infancy: William Adelin, whose fate was a watery grave off the coast of Normandy, and Empress Matilda, wife of the Holy Roman Emperor, Henry V.

A mere five years after the catastrophe of the White Ship, Empress Matilda’s husband died of cancer. A widow without children, she had no leverage to establish a base of power in her late husband’s domains. With limited options, she returned to Normandy, where she was named as successor to her father, King Henry I.

In a time when the rules of succession were both fluid and uncertain, the idea that a woman could inherit was met with some resistance. King Henry I was no fool, and he must have recognized the difficulties which Matilda would face in claiming the throne. In the 60 years since William the Conqueror became William I of England, there had not been one smooth transition of power following the death of a king.

With such difficulties in mind, King Henry I pursued a dual strategy: he remarried following the White Ship disaster, hoping to father another son, and he decided to find a suitable husband for his widowed daughter and current heir – a husband who could help her secure the throne upon his death.

Location, Location, Location: How the County of Anjou Spawned a Dynasty

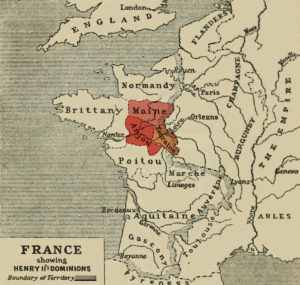

History is replete with tales of how otherwise unremarkable pieces of real estate can wield great influence on the course of events. Although the beauty and resources of Anjou cannot be disputed, it’s location to the south of the Duchy of Normandy put it in the right place at the right time.

After the Norman invasion of 1066, the rise of the Anglo-Norman aristocracy was solidly grounded in the preeminence of the Duchy of Normandy. In many respects, Normandy was the jewel desired by every royal descendant with aspirations for wealth and power. After his ascension to the English throne, Henry I had taken Normandy by force from an older brother, and retaining control of Normandy was paramount to him.

To secure the southern border of Normandy, William Adelin had married the daughter of the Count of Anjou, whose family also controlled the adjacent counties of Maine and Touraine. But with William Adelin’s death, all agreements with Anjou ended. Still desirous of establishing an alliance which would promise peace along Normandy’s southern border, King Henry I arranged for a marriage between his widowed daughter and the eldest son of the Count of Anjou, who was known as Geoffrey Plantagenet – a nickname he received from his habit of wearing a sprig of broom blossom (planta genista) in his hat.

He was 14 years old; she was 26. He was destined to become a count; she had been an empress, and she would proudly retain the title for the rest of her life. His family ruled three landlocked counties; her family took great pride in its glorious Norman heritage. In short, they hated each other.

This unlikely pairing would eventually produce three sons. Regardless of their reputed dislike for one another, Geoffrey would fight tirelessly to secure the throne of England for his wife following the death of her father and the usurpation of the throne by her cousin, Stephen of Blois.

Following the death of King Stephen of Blois in 1154, the oldest son of Count Geoffrey and Empress Matilda ascended to the throne as Henry II, King of England. But first, Henry Plantagenet would accumulate an impressive collection of titles: Duke of Normandy, Count of Anjou and Maine after Geoffrey’s death, and Duke of Aquitaine, by right of wife following his marriage to Eleanor of Aquitaine.

By the time of his ascension to the English throne, Henry possessed a larger proportion of France than the King of France. At the heart of these lands was the County of Anjou – whose people were known as Angevins. Thus, England came to be ruled not by the son of an Anglo-Norman king, but by the son of an Angevin count and his Norman empress.

And it would have never happened if a rock hidden within the murky waters off the coast of Normandy had not claimed the White Ship as its victim.

All images are in the public domain. Modifications of public domain images by J. C. Plummer.

Text © 2017 J.C. Plummer

Posted on

I did not know that the drunken party before setting sail was only a legend, I’ve seen that story in a number of textbooks, but i’ve never heard till now it was only a legend, I suppose that shouldn’t be too surprising though.

Hello! I’m sorry that I’m responding to your comment after so many weeks. I wish the website sent me notices when people leave comments.

In my post, I don’t mean to imply that the drunken party is only a legend – I’m just saying that the drunken party is one of many aspects to the story that can’t be verified with complete certainty after so many centuries and with so few contemporary accounts.

In my opinion (for what it’s worth!) I absolutely believe the drunken party story. Consider that the passengers were young and in a celebratory mood. They were returning to England after something of a “victory lap” through Normandy, where Henry I was reaffirming his control over the duchy.

Thank you so much for reading and leaving a comment!

J.C. (Coleen)