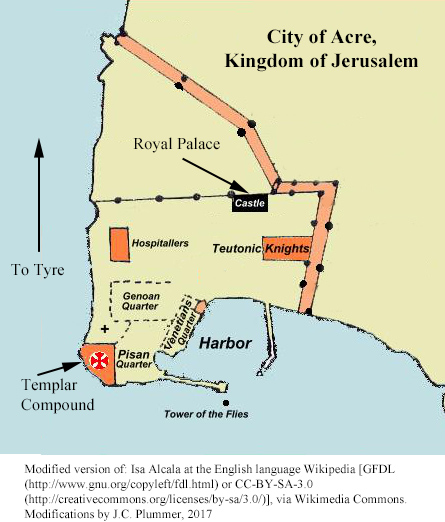

On the night of October 9, 1192, two dozen men stealthily navigated through the ancient streets and alleyways of Acre towards the harbor. King Richard the Lionheart and a select group of his most trusted knights were leaving under the dark canopy of a moonless night. After the men entered the port of Acre, they boarded small boats that would ferry them to the massive buss that awaited just outside the harbor. Their secret departure had been planned for many days, and the people of Acre would awaken to find the fearsome crusader-king and his men gone, much to their dismay.

The previous month, on September 2, 1192, King Richard had signed a three-year truce with the leader of the Saracens, Saladin, ending hostilities and ensuring Christian pilgrims access to the holy sites of Jerusalem, which remained under Saracen control. The Christian Kingdom of Jerusalem was renamed the Kingdom of Acre.

Although Richard had announced his intention to leave the Holy Land and return home, the people of Acre believed that the king would never risk sailing so late in the year. In truth, the people did not want him to leave; having such a skilled military leader in residence was a comfort to them, and many had begged him to remain until spring. They had underestimated King Richard’s resolve to return home by Christmas.

The Lionheart was undaunted by the necessity of sailing west against the prevailing winds and through the inevitable storms of the season, for he knew that the weather was not the only threat he faced in his quest to return to England, Normandy, and the Angevin lands.

Richard had been receiving urgent messages from his mother, Eleanor, advising him to settle his affairs in the Holy Land and return home. His brother, John, was restless and eager to conspire with his enemy, King Philip II of France, who was undermining the Lionheart’s reputation and his authority as king by circulating outrageous stories suggesting that Richard’s behavior during the Crusade had ranged from scandalous to treasonous to blasphemous. He was also accused of hiring mercenaries to murder a political opponent.

In planning his departure from the Holy Land, Richard recognized that not only would he need to leave under cover of darkness to prevent possible riots in the streets of Acre, he would also need to avoid attracting undue attention. Instead of traveling in a swift galley escorted by a fleet of ships filled with men and weapons, Richard selected a large, nondescript buss. His only escorts would be his most trusted men. His plan was to slip into a friendly port along the southern coast of France and quietly enter Aquitaine. From there, he could rapidly move north and cross into England where his mother anxiously awaited his return.

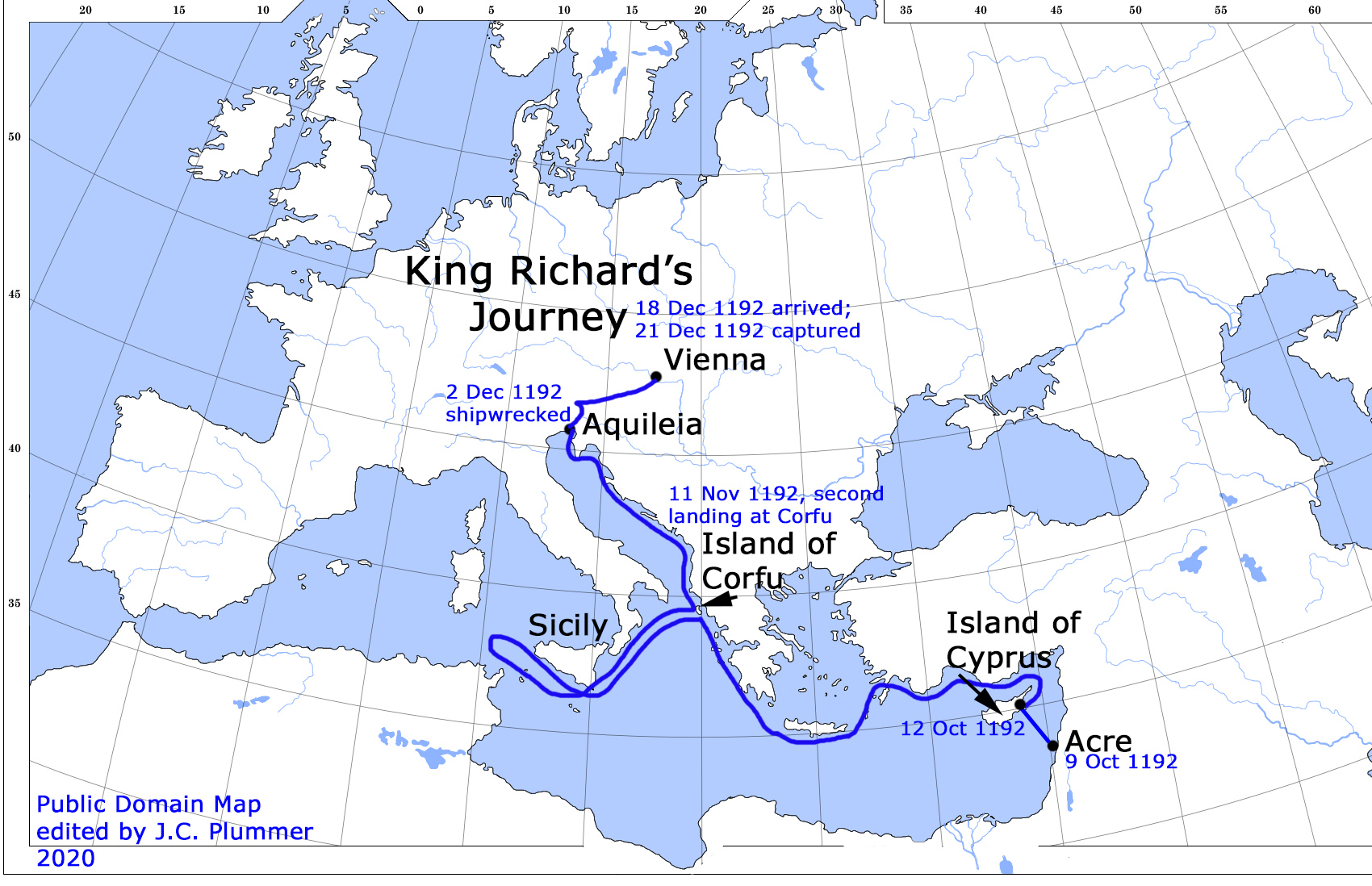

Leaving Acre, the buss hugged the coast as it sailed north towards Tyre. It was typical during this time for passengers to bring their own mattresses and food supplies. Ships would often put ashore every night for fresh food and to allow passengers to rest and cook without fear of setting the boat ablaze. But Richard was in a hurry, and he insisted on sailing day and night, only stopping to take on water and supplies while verifying their position with the locals.

Their first port was Limassol on the island of Cyprus. Already the weather was poor, and the wind was against them. From Cyprus, they continued to stay close to shore as they made their way to Corfu, a large island in the Ionian Sea.

At Corfu, Richard sought information about the potential dangers that might await him as he traveled. It was here that he learned of a meeting between King Philip and the Holy Roman Emperor Henry VI, where Henry promised to arrest Richard if he landed in Italy.

There are disagreements about the next leg of his journey, but most historians believe he sailed to Sicily, where he put into port and discovered that King Philip, working with Count Raymond of Toulouse, had secured the entire southern coast of France. There would be no safe harbor for him there. Likewise, Emperor Henry had sealed the ports of Italy.

Northern Spain was also an impossible choice. The King of Navarre, his father-in-law, was at war with the family ruling the port of Barcelona, and they would happily capture him and hand him over to King Philip.

Although Richard might have considered fighting his way through a harbor town, he only had a small group of men with him. Despite his reputation for daring exploits on the battlefield, even Richard would not have attempted something so foolhardy. If he were captured by an enemy such as King Philip, he could lose everything: England, Normandy, the Angevin lands, and even Aquitaine.

Today, we might suggest passage through the Straits of Gibraltar, but with the sailing technology of the 12th century this would have been impossible—especially since they were traveling against the current, and the current in the straits was faster than the speed of any vessel of the time. Even if they could have navigated through the straits, their ship would first need to travel perilously close to Muslim controlled areas—hardly a prudent risk for a returning crusader!

At this point, there were no good options, but Richard was not a man to give up easily. He was known for his boldness and belief in his own invincibility. He would find another way.

Near Sicily, he sailed along the coast, standing on deck and letting the people on the shore see him. Everyone who saw him would report that King Richard was headed towards southern France.

Under the cover of darkness, the buss turned and sailed back to Corfu.

Returning to Corfu on November 11, 1192, there is uncertainty regarding what transpired next. There are reports of an attack by pirates, where Richard prevailed, but a more likely scenario is that Richard hired two pirate galleys. He planned to sail up the Adriatic Sea and travel across land, through the Alps, in the winter, to reach the territory of his brother-in-law, Henry the Lion of Saxony.

Richard and his closest advisors would be in one galley, and the other would serve as a decoy in case they were attacked.

It was an increasingly desperate journey. They were still traveling through winter storms, only now instead of a large buss, they were in smaller, more delicate ships. Galleys, with their dual propulsion systems (sails and oars), could move faster, but they could not survive in high winds and rough seas.

After a storm in the early morning hours of December 2, Richard’s ship made landfall near the old Roman town of Aquileia.

Richard and his men were in a strange land, in winter, without maps, and none of them spoke the local languages. Over the next nineteen days, they would endure wintry conditions, hunger, lack of sleep, and sickness. They were nearly apprehended on several occasions.

Richard made it as far as Vienna, only 50 miles from his destination in Saxony, before he was captured on December 21, 1192. He would not return to England until March 1194, following his captivity under Emperor Henry.

In Robin Hood’s Widow, the second book in our Robin Hood Trilogy, Robin accompanies King Richard from Acre to Vienna, and readers will follow along during this fateful journey.

By J. C. Plummer, copyright 2020

All images are in the public domain, with modifications as noted.

Glossary Excerpt from Robin Hood’s Widow

buss: A large, fully decked ship with two masts. These ships were capable of carrying nearly 1,000 men, 75 crewmen, horses, and equipment (such as disassembled siege engines).

galley: A type of ship which used rowing as its primary method of propulsion. These ships also had sails. With two methods of propulsion, galleys were versatile and popular for both warfare and trade. Early galleys can be traced as far back as the 8th century BC, and they remained in use throughout the Middle Ages.

Robin Hood’s Dawn is available at Amazon.com and the UK Amazon store.

Robin Hood’s Widow is available at Amazon.com and the UK Amazon store.

Robin Hood’s Return is available at Amazon.com and the UK Amazon Store.

Bibliography

Boyle, David, Troubadour’s Song: The Capture, Imprisonment, and Ransom of Richard the Lionheart, Walker & Company, 2005

Gillingham, John, Richard I, Yale University Press, 1999

McLynn, Frank, Richard and John: Kings at War, Da Capo Press, 2007

Turner, Ralph V. and Heiser, Richard R., The Reign of Richard the Lionheart: Ruler of the Angevin Empire, 1189-1199, Pearson Education Limited, 2000

Posted on

Leave a Reply